Although Seeking the Center is a novel, my motivation for writing the story was, initially, a desire to understand what hockey is. What the hockey life is. Although I made up most aspects of the story—the teams are fictional, the towns are fictional, and the characters, of course, are fictional—I tried to root every made-up detail in reality.

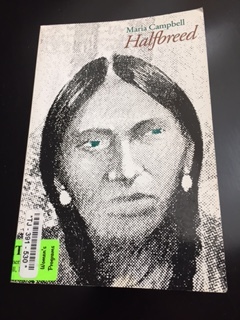

But writing a novel isn’t about reproducing reality, and I’ve come to realize that my need to understand, address, and critique reality sometimes means that my novel’s details aren’t entirely realistic. The character of Claude Doucette (“Deuce”), a Métis enforcer on a minor league hockey team, is a good example of this.

Claude’s family has suffered some recent misfortunes, and he feels obligated to provide them with financial and emotional support. To do so, he often leaves his fictional team in its fictional town in central Saskatchewan and drives north across the prairie to his hometown several hours away. He does this during hockey season, even when he has only one day off. It’s not at all realistic. The distances are huge, and one has to assume that the physical and mental demands placed on pro hockey players would make a trip like this—which Claude does on a fairly regular basis—nearly impossible.

Although unrealistic, these frequent cross-province road trips address at least two topics that I encountered during my research. First, they highlight the fact that professional sport schedules are set up to maximize revenue, while de-prioritizing the personal lives and family relationships of players. Second, there’s the expectation that players should be willing to sacrifice themselves for their team.

In hockey the role of the enforcer represents the extreme of this notion. As an enforcer, Claude’s literal role is to defend his own teammates by fighting the enforcer on the opposing team. Luckily, the harm that this causes to the players involved has become more widely acknowledged in recent years, and actual “enforcers” are much fewer than they were in the ‘90s when Seeking takes place, but the glorification of “taking one for the team” and of fighting itself, persist.

“… I know how much you admire him—how much you admire that kind of player. You know, that big, strong warrior type.”

“I do,” she said.

“The way he’s always, like, camped out in front of the net, taking all that abuse. The way he never turns down a fight. He’s really tough.”

“He is… He’s awesome.”

In Claude’s case, this team/hockey role is echoed or amplified by the roles he plays within his family and community.

“Claude,” asked Agnes, “what did you mean when you said that hockey’s a tough game, but also a tough life?”

“I meant it’s lonely. You’re on the road a lot. Away from the people who care about you.”

She didn’t say anything.

He continued. “You asked about Vin. He’s a good kid, but even if he could get his game back, if he has trouble when he’s living at home, with his family, it’s going to be real tough when he’s away, playing for some team in Alberta, or B.C. Real tough. Trust me.”

They were quiet for a while. Then Agnes said, “you don’t really want to play pro, do you?”

He shrugged. “It’s working out okay so far.”

At one point, Agnes compares him to a (First Nations) chief:

…it didn’t seem like they’d only just met. And the light that washed across his upturned face seemed to shine both inside and out. She felt safe with him. He was just like those old chiefs.

In the character of Claude, the role of enforcer meets the trope of the nearly superhuman First Nations chief, a figure of tremendous character, of mental as well as physical strength, a leader who is there for his people, defending and providing for them no matter the cost to himself. (I wrote about different contexts of “Chief” in an earlier post.)

Agnes thought of Vin, trapped somewhere in the cold maze of hallways, and the old stories flooded her mind, stories of Riel and Big Bear and Poundmaker, the leaders of her people, and how they’d been imprisoned, trapped outside the sun, the cycles, and the seasons —outside of life as they knew it— until they withered.

As a novelist, my goal is neither to hold up this notion of self-sacrifice as the ideal, nor to tear it down completely. I’m not a judge or a philosopher. I’m just trying to portray what I see, to put it out there for consideration, hopefully in an entertaining way.

At five the next morning the sun rose over the horizon and Vin looked out his window to see Claude’s red pickup towing a wooden fishing skiff on an aluminum-frame trailer. Vin stepped out of the door with his hockey bag over his shoulder, his stick in his hand.

“We going fishing?” Vin asked.

“Nah. Already been out.”

“Jesus, Deuce. Do you ever sleep?”

“Sometimes.”

People rarely live up to an ideal. I think this is where my love for Claude, and all my characters, comes in. They are just people, barely bounded by reality, with idiosyncrasies that straddle a wavering line between character and caricature.